- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Postgraduate ethics training programs: a systematic scoping review

BMC Medical Educationvolume21, Article number:338(2021)

Abstract

Background

Molding competent clinicians capable of applying ethics principles in their practice is a challenging task, compounded by wide variations in the teaching and assessment of ethics in the postgraduate setting. Despite these differences, ethics training programs should recognise that the transition from medical students to healthcare professionals entails a longitudinal process where ethics knowledge, skills and identity continue to build and deepen over time with clinical exposure.

A systematic scoping review is proposed to analyse current postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment programs in peer-reviewed literature to guide the development of a local physician training curriculum.

Methods

With a constructivist perspective and relativist lens, this systematic scoping review on postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment will adopt the Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) to create a transparent and reproducible review.

Results

第一个搜索涉及伦理的教学yielded 7669 abstracts with 573 full text articles evaluated and 66 articles included. The second search involving the assessment of ethics identified 9919 abstracts with 333 full text articles reviewed and 29 articles included. The themes identified from the two searches were the goals and objectives, content, pedagogy, enabling and limiting factors of teaching ethics and assessment modalities used. Despite inherent disparities in ethics training programs, they provide a platform for learners to apply knowledge, translating it to skill and eventually becoming part of the identity of the learner. Illustrating the longitudinal nature of ethics training, the spiral curriculum seamlessly integrates and fortifies prevailing ethical knowledge acquired in medical school with the layering of new specialty, clinical and research specific content in professional practice. Various assessment methods are employed with special mention of portfolios as a longitudinal assessment modality that showcase the impact of ethics training on the development of professional identity formation (PIF).

结论s

Our systematic scoping review has elicited key learning points in the teaching and assessment of ethics in the postgraduate setting. However, more research needs to be done on establishing Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA)s in ethics, with further exploration of the use of portfolios and key factors influencing its design, implementation and assessment of PIF and micro-credentialling in ethics practice.

Introduction

Seen as a means of ensuring that “obligations of moral nature which govern the practice of medicine” [1] are maintained, ethics training amongst physicians have evolved to contend with ethical issues facing medical practice. Whilst basic levels of ethics knowledge and skills have been stipulated by accreditation bodies such as The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, The General Medical Council, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), many ethics programs have struggled to keep pace with change whilst remaining sensitive to the demands of clinical practice. Inevitable variations in the content and duration of ethics education amongst physicians have been laid bare in a recent review pertaining to family physicians in residency programs in the United States [2].

有效地教育physicia的试金石ns in ethics knowledge, skills and professional conduct in a medical field trepidatious of legal recourse and struggling to meet public trust and societal expectations [3–7] has perhaps been the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, the surfacing of reports of questionable physician conduct and clinical decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic also offers an opportunity to take stock of prevailing education programs, review gaps in content and structure of ethics education programs as well as update and instil more evidence based, clinically relevant, learner centred education initiatives.

The need for this review

To guide this process of retooling ethics education programs for physicians, a systematic scoping review is proposed to analyse current postgraduate medical ethics training and assessment programs in peer-reviewed literature.

Methodology

我们采用循证appro克里希纳的系统ach (SEBA) to guide this systematic scoping review (henceforth SSRs in SEBA) [8–14广泛的lite)和审查rature [15–17].With its constructivist perspective and relativist lens, SSRs in SEBA map the complex and diverse historical, socio-cultural, ideological and contextual factors that impact practice to provide a holistic picture of medical ethics training programs for graduates beyond medical school [17–24].

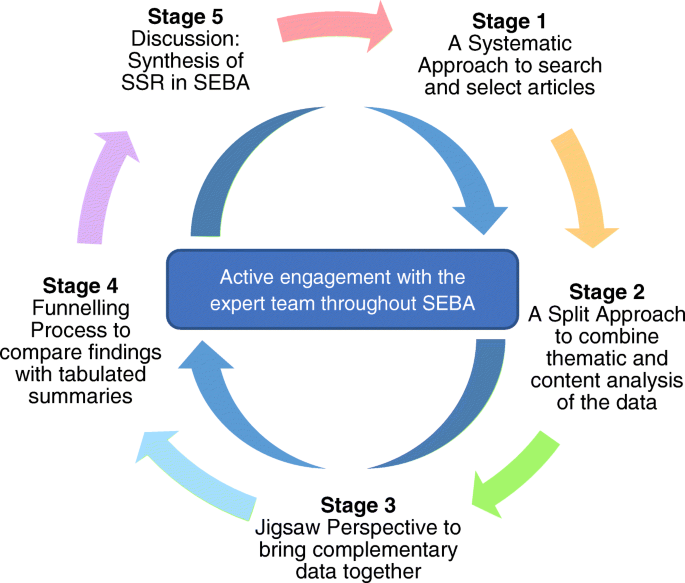

为了进一步提高结果的可靠性,the research team consulted medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and local educational experts and clinicians at NCCS, Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth the expert team). The Systematic Approach, Split Approach, Jigsaw Perspective, , Funnelling Process, and Discussion stages of SEBA (Fig.1. The SEBA Process) were used to guide the entire research process.

Stage 1: Systematic approach

Determining the title and background of the review

The research team consulted the expert team and stakeholders from a local medical ethics training program to determine the overarching goals of the SSR in SEBA as well as the population, context and medical ethics training programs to be evaluated.

Identifying the research question

Guided by the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICOS) elements of the inclusion criteria [25], the primary research question is “How do postgraduate medical training programs teach ethical skills?” The secondary questions are “What are the core topics included?” and “What are the methods used to structure the program in postgraduate training?”

As part of the SEBA methodology’s iterative process, when the initial results of this review were discussed, the expert team advised that a study of current methods of assessing ethics be conducted to address the lack of data on assessments of ethics education. Thus, a second SSR in SEBA was carried out. Similarly guided by PICOS, the primary research question is“How is ethics knowledge, skills, and competencies assessed in postgraduate training?”The secondary question is“What domains are assessed?”

Inclusion criteria

Guided by the expert team, the research team created the inclusion criteria for the SSRs in SEBA for teaching and assessing medical ethics, as outlined (Table1).

Searching

Overall, both searches involved 16 members of the research team who carried out independent searches of PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and ERIC databases for the review. In keeping with Pham, Rajic [26]’s approach to ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, the research team confined the searches to articles published between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2019 to account for prevailing manpower and time constraints. All research methodologies in articles published in English or had English translations were included. The independent searches were carried out between 14 February 2020 and 9 April 2020. The full PubMed search strategy may be found in Additional File1.

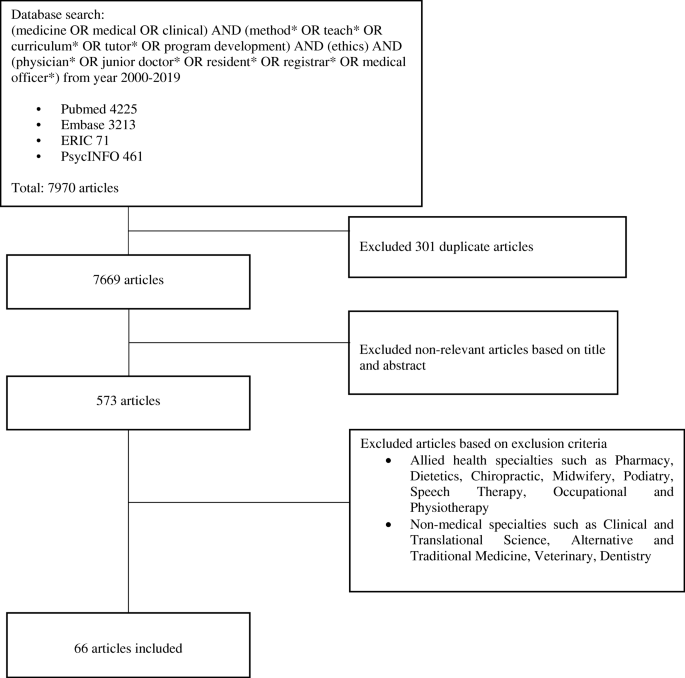

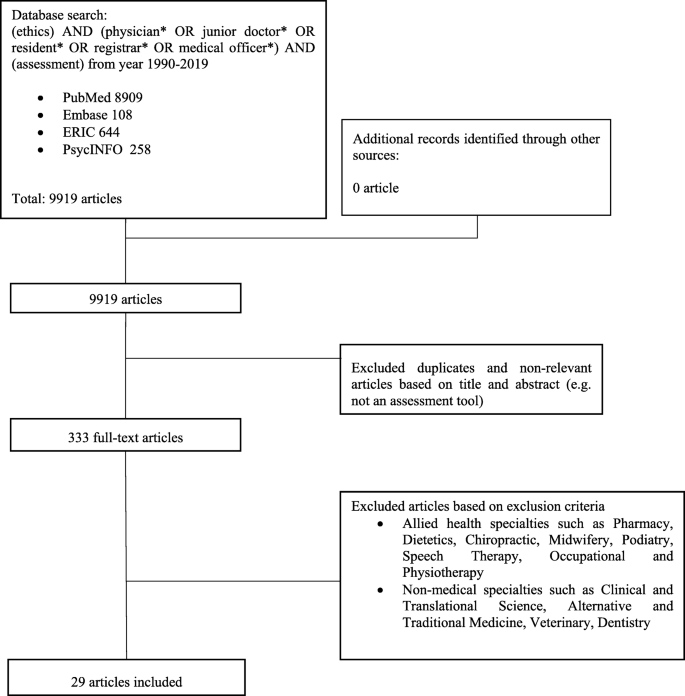

The research team then independently reviewed all the titles on the final list, compared their individual lists of articles to be included in the review and employed ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be analysed on the teaching of ethics (Fig.2.) and assessing of ethics (Fig.3).

Stage 2: Split approach

For each SSR in SEBA, two teams of five researchers concurrently and independently reviewed the full-text articles in keeping with Krishna’s Split Approach that is focused on enhancing the reliability of the analyses [27,28].The first team scrutinised the included articles using Braun and Clarke [29]’s approach to thematic analysis whilst the second team employed Hsieh and Shannon [30]’s approach to directed content analysis. Comparisons between the results of the Split Approach provides method triangulation whilst having each reviewer independently analyse the same data provides investigator triangulation [27,28].Triangulation augments external validity and allows this approach to be more objective.

Braun and Clarke (2006)’s approach to thematic analysis

Without an a priori framework for either teaching or assessing medical ethics amongst physicians, we employed Braun and Clarke’s approach to thematic analysis to single out common themes across varying goals and populations of physicians of different grades, experiences and specialties whilst circumnavigating the context-specific nature of medical ethics in Medicine [29,31–37].It also accommodates for a wide range of research methodologies present amongst the included articles which prevents the use of statistical pooling and analysis [29,38–42] and facilitates appropriate analysis of socio-culturally influenced educational processes such as medical ethics.

‘Codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning of the text through a reiterative step-by-step thematic analysis. These were re-organised into themes that were best able to represent the data. They were reviewed individually and then as a group. Subsequently, the members of this sub-team deliberated their separate findings online and utilised ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final themes.

Hsieh and Shannon (2005)’s approach to directed content analysis

Hsieh and Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis was employed to increase the validity of the themes and to address Braun and Clarke’s relative failure to engage contradictory data.

With regards to the teaching of ethics, the second sub-team drew codes and categories from Sutton [43]’s article entitled ‘伦理s and law teaching and learning in undergraduate medicine’ and McKneally and Singer [44]’s ‘Bioethics for clinicians 25. Teaching bioethics in the clinical setting’.

With regards to the assessing of ethics, codes and categories from Norcini, Anderson [35]’s‘Draft 2018 Consensus Framework for Good Assessment’, Veloski, Boex [45]‘s ‘Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7′ and Watling and Ginsburg [46]’s‘Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning’were used.

这些代码是作为一个框架进行审查ing the included articles. Any relevant data not captured by existing codes were assigned a new code through deductive category application. The independent findings were discussed online and ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was again used to achieve consensus on the final ‘code book’.

Stage 3: The jigsaw perspective

The findings of the Split Approach and its reiterative process were then pooled together to ensure a well-rounded perspective of the data. Here, common themes and categories within each SSR were compared. Overlaps between the categories and themes were combined to create a wider perspective of the data, much like bringing together complementary pieces of a jigsaw. This process is called the Jigsaw Perspective and is overseen by the expert team to ensure consistency.

Results

第一个搜索涉及伦理的教学retrieved 7669 abstracts, with 573 full-text articles reviewed and 66 articles included. Comparison of the categories and themes identified as part of the Split Approach revealed similar categories and themes which were combined into themes/categories using the Jigsaw Perspective. These themes/categories include the goals, content, teaching methods employed, and enablers and barriers to teaching ethics.

For the assessment of ethics, the search saw 9919 abstracts identified, 333 full-text articles reviewed and 29 articles included. The Split Approach from the SSR in SEBA of assessment methods revealed three themes/categories which included the types and domains assessed and the pros and cons of various assessment methods.

Stage 4: The funnelling process

In addition, a third sub-team summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles to ensure that important concepts of discussion and contradictory views within the included articles were retained. The tabulated summaries also serve to verify that the results ascertained are an accurate representation of the existing data. The tabulated summaries for the teaching and assessing of ethics may be found in Additional File 2 and 3 respectively. Under the oversight of the expert team, the research team combined themes/categories from the two SSRs in SEBA based upon their similarities and their areas of overlap in keeping with the Funnelling Process.

The five funnelled themes/categories from the two searches are the goals and objectives, the content, pedagogy, enabling and limiting factors, and assessment tools.

Goals and objectives

The goals and objectives of ethics training programs for doctors are highlighted in Table2below.

Overall, the goal of most ethics programs was to refresh key ethical principles covered in medical schools [51], prepare physicians to tackle ethical dilemmas, and improve their confidence in doing so [59,71,77].Some programs also introduced context and specialty-specific ethical dilemmas as highlighted in the next section on content covered [48,53,56,70,78–80].

Content covered

Content covered is outlined in Table3.

Most training programs covered a varying number of topics.

Whilst Carrese, Malek [96] noted an overlap in the range of topics covered in ethics training for doctors and those for medical students, the authors explain that “educational materials offered to residents can typically be more complex and contextual than those intended for medical students, and ethical issues can be more nuanced and discussed in greater depth”.

Pedagogy

The diverse pedagogies are highlighted in Table4below.

There is great variation in the timing and duration of such training sessions. Formal teaching run by the host organisation or institution tended to come in the form of mandatory training programmes [80,81] that span the course of a few years [62,82] or a single day [67].Some programs are held over a few hours each year [58,94], or each month or every few months as part of a wider residency training program [49,59,83].

Informal programs tended to be situated in more informal settings where refreshments are served and hierarchies are minimised [49,59].

Different training programs utilised a combination of approaches to meet their objectives [82].At the University of Toronto, Howard, McKneally [70] describes integrating formal bioethics teaching with “role modelling of ethical behaviour and bedside teaching around ethical issues”. The impact of this combination is echoed by Lang, Smith [97]’s survey of paediatric programme directors on how ethics is taught. Carrese, Malek [96]’s literature review of medical ethics training similarly highlighted the synergistic nature of the formal, informal and hidden curricula [77].

Other authors have proffered the use of a multidisciplinary approach to illustrate the intricacies of team based working in the healthcare setting [59,69,73,101,102].

Enabling factors and barriers

Enabling factors and barriers to the successful execution of ethics training programs may present themselves as follows (Table5):

Believing that new learners often “do not appreciate the practical side of ethical conflicts as they have had limited exposure to clinical medicine or have not yet fully formed a professional identity with its associated values,” Grace and Kirkpatrick [68] piloted ethical vignettes and ethical reasoning technique to acculturate ethical thinking into practice. Howard, McKneally [84]’s study of surgical resident’s attitudes towards ethics teaching revealed a general sense of being poorly prepared and relatively inexperienced for case discussions and practical application of ethical issues.

Carrese, McDonald [60] and Chandra, Ragesh [69] also note that even in the event that ethical issues did arise, they were poorly modelled and rarely used as teaching moments.

Assessment tools

Assessment tools comprise the type of assessment method employed, corresponding domains assessed and their pros and cons (Table6). These assessment methods may be mapped onto the Miller’s pyramid of clinical competency [131].

Stage 5: Discussion and synthesis of SSRs in SEBA

A review of the results and consultation with local educationalists, clinicians and researchers experienced in medical ethics teaching and assessment reiterated the completeness of this review. The narrative produced was guided by the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement [38] and Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide [39].This novel review of teaching and assessment of ethics amongst physicians reveals a number of insights. Here we list some of the key findings for ease of reference and will delve into three areas of particular interest.

The common objective across most ethics programs is to improve awareness of ethical principles and skills in resolving ethical dilemmas tactfully and professionally. More recent articles however focused on changing practice, shaping attitudes and meeting social and professional obligations.

Recent accounts of teaching and assessing ethics reveal the impact of context and speciality related influences.

The core elements of most programs concerned the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice; the doctor- patient relationship; communication; and end of life care.

Speciality or context specific information contents include research ethics; speciality related topics; trainee related considerations and social and or institutional interactions.

There were a number of approaches employed to teach ethics yet all were focused upon providing learners with an opportunity to apply their knowledge in a variety of ways, ranging from optional participation in group discussions to guided case discussions and reflections.

Factors facilitating ethics education and assessments were a structured program, a nurturing culture and a safe environment to discuss concerns and enquiries.

Important in ethics training are role modelling, case-based discussions and instruction on ethical sensitivity and resolving ethical issues.

There is a general lack of assessment methods.

While there are inherent differences to each of the training programs, they may be seen to lie on a continuum of guiding the learner from knowledge building to practice and ultimately to nurturing the learner’s professional identity. Indeed, many programs seek to prepare learners for their societal responsibilities [49,60,70–76,85] and their membership to their ‘community of practice’ [69,70].This would be consistent with Cruess, Cruess [131]’s “Is” level at the apex of their amended Miller’s pyramid. With this in mind, evidence for this posit is visible from the contents and manner that ethics education is taught.

Careful study of the longitudinal nature of training programs, the presence of refresher sessions and/or sessions involving ‘core’ topics such as autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, end of life care,the doctor patient relationship and the duty of care suggests a reinforcement of prevailing knowledge [48,50,51,56,57,59,67,73,81,82,86,97,98].The introduction of more specialised speciality, clinical and research content suggests a layering of new knowledge and experiential learning. This process of building on prevailing knowledge evidences the longitudinal nature of training that would seem to build on training received in medical school and efforts to deepen appreciation of ethical issues in the clinical setting. This is also evidenced by the methods used to train the learners. Here didactic lectures, online videos and bedside ethics discussions give way to case discussions and presentations, allowing the learner to build their knowledge and confidence and apply their knowledge and skills in addressing the ethical issues [58,69,74,78,86,99].

These considerations also highlight the vertical aspect of the spiral curriculum employed by most programs and raise the importance of knowledge and skills assessments. Evidence that ethical training is introduced at specific stages of practice such as during postings where end of life care is especially relevant, or where discussions of withdrawing and withholding life sustaining treatment, such as intensive care placements, suggest horizontal integration of the ethics training programs.

The presence of a spiral curriculum that seeks to build on prevailing knowledge and integrate context specific learning highlights two considerations. The first is the use of pertinent assessments to determine progress to the next stage of the training and the second is the support of the program by the host organizsation.

Training should be followed by assessments to ensure that knowledge has been effectively assimilated and applied appropriately, and to facilitate micro-credentialling, as suggested by Norcini [132].同时,也有必要establish clear Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA) s in ethics education which, at present, will require further research and consideration given the diversity of practice, specialities, socio-cultural considerations and learner variability in terms of their prevailing knowledge, skills, attitudes and experience [133].The need for a longitudinal assessment process as a part of an education portfolio and their impact on the development of professional identity formation (PIF) also demands closer scrutiny [131,134].

Here, learning portfolios will allow seamless integration between ethics training in undergraduate and postgraduate training [51,83,97,98] and would be in keeping with the notion of ethics training being part of a longitudinal training experience [4,135] that nurtures PIF [131,134].Portfolios not only serve as a valuable assessment modality for longitudinal evaluation of ethical competency but also promotes continuous self-learning through the recognition of knowledge deficits while reinforcing good behaviour [63,136–143].

Yet an effective ethics training program requires support fromresidency programs, healthcare institutes and educational institutes through the allocation ofallocating dedicated resources, manpower and faculty training [64,70,79].The host organisation must orchestrate this training and provide careful oversight of the program's trajectory. Perhaps just as important is that there are efforts to ensure that clinicians acknowledge and adopt their roles and responsibilities in their ‘communities of practice’ [144].The topics chosen should be practical and feasibly covered within the limited time allotted yet be relevant to clinical practice [52,55,59,60,73,79,83,96–98].

The programs and host organisations must also instil a nurturing ethical climate through the dissemination of core values and introduction of infrastructure that “proactively incorporates these values in the daily life of the healthcare organi[z]ations” [145].An ethical climate would aid in professional identity formation [131,134,146].

Limitations

Whilst it was our intention to appreciate the range of available literature on ethics education in postgraduate medical education, it is evident that each paper could be studied in greater depth. This limitation is mainly due to incomplete reporting of the current training approaches and their curriculum, as well as the way in which the programs are is carried out and evaluated.

Furthermore, the range of selected articles chosen originates from papers that were largely written in North America and Europe. This limits the applicability of these findings, as the different cultures across the different geographical boundaries are not accounted for.

However, despite these limitations, this scoping review was carried out with the necessary rigour and transparency advocated by Arksey and O’Malley [21], Pham, Rajic [26], and Levac, Colquhoun [147].The use of Endnote, a bibliographic manager, ensured that all the citations from the different databases were properly accounted for.

结论

We believe the analysis of our findings in this scoping review will be relevant to educators and program designers in postgraduate medical settings around the world. However, the lack of consensus and difference in perspectives regarding the approach, content and quality assessments as well as the need to explore the inherent link amongst ethics, communication and professionalism [63,148,149] justifies inclusion of programs focused on enhancing communication skills and professionalism in medicine. In addition, more needs to be done to research on establishing EPAs in ethics amidst the diverse characteristics of learners, their settings and their levels of experience as well as the particular healthcare system and culture that they practice in. Research should also look into portfolio design, implementation and assessment of PIF and micro-credentialling in ethics practice in the postgraduate setting.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article [and its additional files].

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EPA:

-

Entrustable professional activities

- SEBA:

-

Systematic evidence-based approach

- SSR:

-

Systematic scoping review

- YLLSoM:

-

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

- NUS:

-

National University of Singapore

- NCCS:

-

National Cancer Centre Singapore

- PICOS:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome

- STORIES:

-

Structured approach to the reporting in healthcare education of evidence synthesis

- BEME:

-

Best evidence medical education

- PIF:

-

Professional identity formation

References

Brunt PW. Dictionary of medical ethics (2nd edn). Edited by A. S. Duncan, G. R. Dunstan and R. B. Welbourn. (Darton, Longman and Todd, London, 1981.) £12.50. - Contemporary issues in biomedical ethics. Edited by J. W. Davis, B. Hoffmaster and S. Shorten. (Humana press, Clifton, New Jersey, 1981.) £11.15. J Biosoc Sci. 1982;14(3):374–6.

Manson HM, Satin D, Nelson V, Vadiveloo T. Ethics education in family medicine training in the United States: a national survey. Fam Med. 2014;46(1):28–35.

Campbell AV. The teaching of medical ethics. Med Teach. 2011;33(5):349–50.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.571728.

Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: where are we? Where should we be going? A review. Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1143–52.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020.

Millstone M. Teaching medical ethics to meet the realities of a changing health care system. J Bioeth Inq. 2014;11(2):213–21.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-014-9520-9.

Pellegrino ED. Teaching medical ethics: some persistent questions and some responses. Acad Med. 1989;64(12):701–3.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198912000-00002.

Sokol DK. Teaching medical ethics: useful or useless? BMJ. 2016:i6415.

Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Kamal N, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):246.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02169-3.

Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, Ong ZH, Ghazali HZB, Tan LHE, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x.

Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek JTY, Chia JL, Chan NPX, et al. Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;1049909120950301.

Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, Tay KT, Hee JM, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649.

Nur Haidah Ahmad Kamal LHET, Wong RSM, Ong RRS, Ryan Ern Wei Seow EKYL, Mah ZH, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliat Med Care Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–11.

Ryan Rui Song Ong REWS, Wong RSM. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–22.

Zheng Hui Mah RSMW, Loh REWSEKY, Haidah N, Ahmad Kamal RRSO, Tan LHE, Chiam M, et al. A systematic scoping review of systematic reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care Open Access. 2020;7(1):1–12.

Boden C, Ascher MT, Eldredge JD. Learning while doing: program evaluation of the medical library association systematic review project. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(3):284–93.https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.286.

Hinchcliff R,格林菲尔德D,摩尔多瓦M,韦斯特布鲁克JI, Pawsey M, Mumford V, et al. Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(12):979–91.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000852.

Nicholas Mays ER, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. Studying the organization and delivery of health services: research methods. London: Routledge; 2001. p. 2001.

Horsley T. Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2019;39(1):54–7.https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000241.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2002;8(1):19–32.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Lorenzetti DLPS. A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. J Acad Librariansh. 2015;41(2):186–96.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.12.001.

Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):54.https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-54.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123.

Wen Jie Chua CWSC, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LKR. Structuring mentoring in medicine and surgery. A systematic scoping review of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2020;40(3):158–68.

Yong Xiang Ng ZYKK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, Tan LHE, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2014;36(1):47–61.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.850154.

Goldie J. Assessment of professionalism: a consolidation of current thinking. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):e952–6.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714888.

Hodges B, Paul R, Ginsburg S, The Ottawa Consensus Group M. Assessment of professionalism: from where have we come - to where are we going? An update from the Ottawa Consensus Group on the assessment of professionalism. Med Teach. 2019;41(3):249–55.https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1543862.

Li H, Ding N, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wen D. Assessing medical professionalism: a systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177321.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177321.

Norcini J, Anderson MB, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa MJ, Duvivier R, et al. 2018 consensus framework for good assessment. Med Teach. 2018;40(11):1102–9.https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016.

Patterson F, Roberts C, Hanson MD, Hampe W, Eva K, Ponnamperuma G, et al. 2018 Ottawa consensus statement: selection and recruitment to the healthcare professions. Med Teach. 2018;40(11):1091–101.https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1498589.

Van Der Vleuten CPMSL. Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Med Educ. 2005;39(3):309–17.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02094.x.

Gordon MGT. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):143.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0143-0.

Haig A, Dozier M. BEME guide no. 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 2: constructing searches. Med Teach. 2003;25(5):463–84.https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001608667.

Riquelme A, Herrera C, Aranis C, Oporto J, Padilla O. Psychometric analyses and internal consistency of the PHEEM questionnaire to measure the clinical learning environment in the clerkship of a Medical School in Chile. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e221–5.https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590902866226.

Schonrock-Adema J, Heijne-Penninga M, Van Hell EA, Cohen-Schotanus J. Necessary steps in factor analysis: enhancing validation studies of educational instruments. The PHEEM applied to clerks as an example. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e226–32.https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802516756.

Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):947–52.https://doi.org/10.3109/01421591003686229.

Sutton A. Ethics and law teaching and learning in undergraduate medicine. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(8):511.https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.036350.

McKneally MF, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: 25. Teaching bioethics in the clinical setting. CMAJ. 2001;164(8):1163–7.

Veloski J, Boex JR, Grasberger MJ, Evans A, Wolfson DB. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7. Med Teach. 2006;28(2):117–28.https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600622665.

•沃CJ、金斯伯格s评估费用dback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):76–85.https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13645.

Sim K, Sum MY, Navedo D. Use of narratives to enhance learning of research ethics in residents and researchers. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):41.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0329-y.

Stoff BK, Grant-Kels JM, Brodell RT, Paller AS, Perlis CS, Mostow E, et al. Introducing a curriculum in ethics and professionalism for dermatology residencies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):1032–4.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1121.

Bercovitch L, Long TP. Dermatoethics: a curriculum in bioethics and professionalism for dermatology residents at Brown Medical School. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):679–82.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.016.

Jain S, Dunn LB, Warner CH, Roberts LW. Results of a multisite survey of U.S. psychiatry residents on education in professionalism and ethics. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):175–83.https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.35.3.175.

Vertrees SM, Shuman AG, Fins JJ. Learning by doing: effectively incorporating ethics education into residency training. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(4):578–82.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2277-0.

Bercovitch L, Long TP. Ethics education for dermatology residents. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(4):405–10.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.02.015.

Daniel Z, Buchman ELB, Iles J. Core strategies for the development of a clinical neuroethics education program for medical residents in the clinical neurosciences. J Ethics Ment Health. 2009;4(2):1–6.

Hendee W, Bosma JL, Bresolin LB, Berlin L, Bryan RN, Gunderman RB. Web modules on professionalism and ethics. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(3):170–3.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2011.11.014.

Lennon-Dearing R,洛瑞LW,罗斯CW,戴尔基于“增大化现实”技术,一个我nterprofessional course in bioethics: training for real-world dilemmas. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(6):574–85.https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820902921621.

Mehta P, Hester M, Safar AM, Thompson R. Ethics-in-oncology forums. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22(3):159–64.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03174329.

Tolchin B, Willey JZ, Prager K. Education research: a case-based bioethics curriculum for neurology residents. Neurology. 2015;84(13):e91–3.https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001412.

Wada K, Doering M, Rudnick A. Ethics education for psychiatry residents. A mixed-design retrospective evaluation of an introductory course and a quarterly seminar. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2013;22(4):425–35.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180113000339.

Klingensmith ME. Teaching ethics in surgical training programs using a case-based format. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(2):126–8.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.12.001.

Carrese JA, McDonald EL, Moon M, Taylor HA, Khaira K, Catherine Beach M, et al. Everyday ethics in internal medicine resident clinic: an opportunity to teach. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):712–21.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03931.x.

Lipworth W, Kerridge I, Little M, Gordon J, Markham P. Meaning and value in medical school curricula. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(5):1027–35.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01912.x.

Salih ZN, Boyle DW. Ethics education in neonatal-perinatal medicine in the United States. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33(6):397–404.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2009.07.008.

Daboval T, Moore GP, Ferretti E. How we teach ethics and communication during a Canadian neonatal perinatal medicine residency: an interactive experience. Med Teach. 2013;35(3):194–200.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.733452.

Liu EY, Batten JN, Merrell SB, Shafer A. The long-term impact of a comprehensive scholarly concentration program in biomedical ethics and medical humanities. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):204.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1311-2.

Sherman HB, McGaghie WC, Unti SM, Thomas JX. Teaching pediatrics residents how to obtain informed consent. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S10–3.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-00006.

Vora MBSC. Effectiveness of workshop training in basic principles of good clinical practice among the medical teachers - a cross sectional study. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;1(2):92–6.

Ramalingam S, Bhuvaneswari S, Sankaran R. Ethics workshops-are they effective in improving the competencies of faculty and postgraduates? J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(7):XC01–XC3.https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/8825.4561.

Grace AJ, Kirkpatrick HA. Teaching ethics that honor the patient's and the provider's voice: the role of clinical integrity. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2018;53(5–6):445–54.https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217418791445.

Chandra PS, Ragesh G, Chaturvedi SK. Ten-minute snapshots - a team approach to teaching postgraduates about professional dilemmas. Indian J Med Ethics. 2017;2(4):226–30.https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2017.052.

Howard F, McKneally MF, Levin AV. Integrating bioethics into postgraduate medical education: the University of Toronto model. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):1035–40.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbebb8.

Cook AFRL. Young physicians’ recall about pediatric training in ethics and professionalism and its practical utility. 2013;163(4):1196–201.

Cummings CL. Teaching and assessing ethics in the newborn ICU. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(4):261–9.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2015.12.016.

Helft PR, Eckles RE, Torbeck L. Ethics education in surgical residency programs: a review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(1):35–42.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.10.001.

Matos FM, Raemer DB. Mixed-realism simulation of adverse event disclosure: an educational methodology and assessment instrument. Simul Healthc. 2013;8(2):84–90.https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e31827cbb27.

Oljeski SA, Homer MJ, Krackov WS. Incorporating ethics education into the radiology residency curriculum: a model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(3):569–72.https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830569.

Steinemann S, Furoy D, Yost F, Furumoto N, Lam G, Murayama K. Marriage of professional and technical tasks: a strategy to improve obtaining informed consent. Am J Surg. 2006;191(5):696–700.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.003.

Kesselheim JC, Najita J, Morley D, Bair E, Joffe S. Ethics knowledge of recent paediatric residency graduates: the role of residency ethics curricula. J Med Ethics. 2016;42(12):809–14.https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103625.

Belling C, Coulehan J. A window of opportunity: ethics and professionalism in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(4):326–9.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1804_9.

Byrne J, Straub H, DiGiovanni L, Chor J. Evaluation of ethics education in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):397 e1–8.

Ghias K, Ahmer S. Guarding the guardians: bioethics curricula for psychiatrists-in-training in developing countries. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):294–300.https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.482096.

Grossman E, Posner MC, Angelos P. Ethics education in surgical residency: past, present, and future. Surgery. 2010;147(1):114–9.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.011.

Bennett KG, Ingraham JM, Schneider LF, Saadeh PB, Vercler CJ. The teaching of ethics and professionalism in plastic surgery residency: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78(5):552–6.https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000000919.

Tsao CI, Guedet PJ. Ethics and professionalism preparation for psychiatrists-in-training: a curricular proposal. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):301–5.https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.482095.

Howard F, McKneally MF, Upshur RE, Levin AV. The formal and informal surgical ethics curriculum: views of resident and staff surgeons in Toronto. Am J Surg. 2012;203(2):258–65.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.02.008.

Robb A, Etchells E, Cusimano MD, Cohen R, Singer PA, McKneally M. A randomized trial of teaching bioethics to surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2005;189(4):453–7.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.08.066.

Cheung L. Creating an ethics curriculum using a structured framework. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:142–3.https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.58ed.e607.

Huijer M, van Leeuwen E, Boenink A, Kimsma G. Medical students’ cases as an empirical basis for teaching clinical ethics. Acad Med. 2000;75(8):834–9.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200008000-00017.

Steinemann D, Skawran B, Becker T, Tauscher M, Weigmann A, Wingen L, et al. Assessment of differentiation and progression of hepatic tumors using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(10):1283–91.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.010.

Walsh BC, Karia R, Egol K, Zuckerman JD, Phillips D. Teaching professionalism in orthopaedic residency: efficacy of the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons ethics modules. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(14):507–14.https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00386.

Goold SD, Stern DT. Ethics and professionalism: what does a resident need to learn? Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(4):9–17.https://doi.org/10.1080/15265160600755409.

Gupta M, Forlini C, Lenton K, Duchen R, Lohfeld L. The hidden ethics curriculum in two Canadian psychiatry residency programs: a qualitative study. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(4):592–9.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0456-0.

今敏AA。Resident-generated与instructor-generated cases in ethics and professionalism training. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2006;1(1):E10.

Taylor HA, McDonald EL, Moon M, Hughes MT, Carrese JA. Teaching ethics to paediatrics residents: the centrality of the therapeutic alliance. Med Educ. 2009;43(10):952–9.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03449.x.

McClean KL, Card SE. Informed consent skills in internal medicine residency: how are residents taught, and what do they learn? Acad Med. 2004;79(2):128–33.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200402000-00006.

Brajenovic-Milic B, Ristic S, Kern J, Vuletic S, Ostojic S, Kapovic M. The effect of a compulsory curriculum on ethical attitudes of medical students. Coll Antropol. 2000;24(1):47–52.

Carrese JA, Malek J, Watson K, Lehmann LS, Green MJ, McCullough LB, et al. The essential role of medical ethics education in achieving professionalism: the Romanell report. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):744–52.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000715.

Lang CW, Smith PJ, Ross LF. Ethics and professionalism in the pediatric curriculum: a survey of pediatric program directors. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1143–51.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0658.

Moreno Villares JMGCE. An ethics curriculum for the pediatric residency program: experience of a university hospital. An Pediatr. 2003;58(4):333–8.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1695-4033(03)78067-9.

Goodrich TJIC, Boccher-Lattimore D. Narrative ethics as collaboration: a four-session curriculum. Fam Syst Health. 2005;23(3):348–57.https://doi.org/10.1037/1091-7527.23.3.348.

Beresin EV, Baldessarini RJ, Alpert J, Rosenbaum J. Teaching ethics of psychopharmacology research in psychiatric residency training programs. Psychopharmacology. 2003;171(1):105–11.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1434-x.

Benbassat J, Baumal R. What is empathy, and how can it be promoted during clinical clerkships? Acad Med. 2004;79(9):832–9.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200409000-00004.

Buchman DZ, Russell BJ. Addictions, autonomy and so much more: a reply to Caplan. Addiction. 2009;104(6):1053–4 author reply 4-5.

Al-Mahroos F, Bandaranayake RC. Teaching medical ethics in medical schools. Ann Saudi Med. 2003;23(1–2):1–5.https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2003.1.

Bentwich ME, Bokek-Cohen Y. Process factors facilitating and inhibiting medical ethics teaching in small groups. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(11):771–7.https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103947.

Kanter SL, Wimmers PF, Levine AS. In-depth learning: one school's initiatives to foster integration of ethics, values, and the human dimensions of medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(4):405–9.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318033373c.

Kong WM, Knight S. Bridging the education-action gap: a near-peer case-based undergraduate ethics teaching programme. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(10):692–6.https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103762.

Robeson R, King NMP. Performable case studies in ethics education. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5(3).

Lewin LO, Lanken PN. Longitudinal small-group learning during the first clinical year. Fam Med. 2004;36(Suppl):S83–8.

Tsai TC, Harasym PH. A medical ethical reasoning model and its contributions to medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(9):864–73.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03722.x.

Wasson K, Bading E, Hardt J, Hatchett L, Kuczewski MG, McCarthy M, et al. Physician, know thyself: the role of reflection in bioethics and professionalism education. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2015;5(1):77–86.https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2015.0019.

Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861–71.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001.

Patrinely JR Jr, Drolet BC, Perdikis G, Janis J. Ethics education in plastic surgery training programs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(3):532e–3e.

Andre J, Brody H, Fleck L, Thomason C, Tomlinson T. Ethics, professionalism, and humanities at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(10):968–72.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200310000-00005.

Lehmann LS, Kasoff WS, Koch P, Federman DD. A survey of medical ethics education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2004;79(7):682–9.https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200407000-00015.

Cohn JM. Bioethics curriculum for paediatrics residents: implementation and evaluation. Med Educ. 2005;39(5):530.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02152.x.

Lohfeld L, Goldie J, Schwartz L, Eva K, Cotton P, Morrison J, et al. Testing the validity of a scenario-based questionnaire to assess the ethical sensitivity of undergraduate medical students. Med Teach. 2012;34(8):635–42.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687845.

Malek J, Geller G, Sugarman J. Talking about cases in bioethics: the effect of an intensive course on health care professionals. J Med Ethics. 2000;26(2):131–6.https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.26.2.131.

Tsai TC, Harasym PH, Coderre S, McLaughlin K, Donnon T. Assessing ethical problem solving by reasoning rather than decision making. Med Educ. 2009;43(12):1188–97.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03516.x.

Viswanath B, Jayarajan RN,钱德拉PS, Chaturvedi SK. Supplementing research ethics training in psychiatry residents: a five-tier approach. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;34:54–6.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2018.04.003.

Fanous A, Rappaport J, Young M, Park YS, Manoukian J, Nguyen LHP. A longitudinal simulation-based ethical-legal curriculum for otolaryngology residents. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(11):2501–9.https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26551.

Moon MR, Hughes MT, Chen JY, Khaira K, Lipsett P, Carrese JA. Ethics skills laboratory experience for surgery interns. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):829–38.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.03.010.

Moore GP, Ferretti E, Daboval T. Developing a knowledge test for a neonatal ethics teaching program. Cureus. 2017;9(12):e1971.https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1971.

Strong C, Beckmann CR, Dacus JV. A conference on ethics for obstetric and gynaecological clerkship students. Med Educ. 1992;26(5):354–9.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00185.x.

Sulmasy DP, Geller G, Levine DM, Faden RR. A randomized trial of ethics education for medical house officers. J Med Ethics. 1993;19(3):157–63.https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.19.3.157.

Kotzee B, Ignatowicz A. Measuring ‘virtue’ in medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 2016;19(2):149–61.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-015-9653-6.

Pauls MA. Teaching and evaluation of ethics and professionalism: in Canadian family medicine residency programs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(12):e751–6.

Cook AF, Sobotka SA, Ross LF. Teaching and assessment of ethics and professionalism: a survey of pediatric program directors. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6):570–6.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.07.009.

Dingle AD, Kolli V. Ethics in child and adolescent psychiatry training: what and how are we teaching? Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(2):168–78.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01149-0.

Mohamed AM, Ghanem MA, Kassem A. Knowledge, perceptions and practices towards medical ethics among physician residents of University of Alexandria Hospitals, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(9):935–45.https://doi.org/10.26719/2012.18.9.935.

Pascual-Ramos V, Contreras-Yanez I, Arce Salinas CA, Saavedra Salinas MA, Del Mercado M, Lopez Zepeda J, et al. Evaluation of medical ethics competencies in rheumatology: local experience during national accreditation process. J Med Ethics. 2019;45(12):839–42.https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2019-105717.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller's pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):180–5.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913.

Norcini J. Is it time for a new model of education in the health professions? Med Educ. 2020;54(8):687–90.https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14036.

Ten Cate O, Taylor DR. The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140. Med Teach. 2020:1–9.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446–51.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427.

de la加尔萨年代,港区V, Throneberry年代,布卢门撒尔-Barby J, McCullough L, Coverdale J. Teaching medical ethics in graduate and undergraduate medical education: a systematic review of effectiveness. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(4):520–5.https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0608-x.

Challis M. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 11 (revised): portfolio-based learning and assessment in medical education. Med Teach. 1999;21(4):370–86.

Mathers NJ, Challis MC, Howe AC, Field NJ. Portfolios in continuing medical education--effective and efficient? Med Educ. 1999;33(7):521–30.https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00407.x.

Dawe R, Pike A, Kidd M, Janakiram P, Nicolle E, Allison J. Enhanced skills in global health and health equity: guidelines for curriculum development. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(2):e48–60.https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.36885.

Fins JJ, Kodish E, Cohn F, Danis M, Derse AR, Dubler NN, et al. A pilot evaluation of portfolios for quality attestation of clinical ethics consultants. Am J Bioeth. 2016;16(3):15–24.https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2015.1134705.

Robert M, Jarvis PSOS, McClain T, Clardy JA. Can one portfolio measure the six ACGME general competencies? Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):190–6.

Jenkins L, Mash B, Derese A. Development of a portfolio of learning for postgraduate family medicine training in South Africa: a Delphi study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):11.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-11.

O'Sullivan P, Greene C. Portfolios: possibilities for addressing emergency medicine resident competencies. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1305–9.https://doi.org/10.1197/aemj.9.11.1305.

Watling CJ, Brown JB. Education research: communication skills for neurology residents: structured teaching and reflective practice. Neurology. 2007;69(22):E20–6.https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000280461.96059.44.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185–91.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826.

Silverman HJ. Organizational ethics in healthcare organizations: proactively managing the ethical climate to ensure organizational integrity. HEC Forum. 2000;12(3):202–15.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008985411047.

Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185–90.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–92.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3.

Frank JR, MMEF. The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DZH, JLG, ZYO, JJQT, MKW, JW, XHT, RQET, CLLC, CWHN, JCKN, YTO, CWSC, KTT, LHST, GLGP, WF, LW, SHSN, ASIL, MC, AMCC, LKRK were involved in research design and planning, investigation, analysis, reflection, manuscript writing and review, and administrative work for journal submission. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

伦理s declarations

伦理s approval and consent to participate

NA

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Full PubMed Search Strategy.

Additional file 2.

Tabulated Summaries for Teaching of Ethics.

Additional file 3.

Tabulated Summaries for Assessing of Ethics.

Rights and permissions

Open AccessThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, D.Z., Goh, J.L., Ong, Z.Y.et al.Postgraduate ethics training programs: a systematic scoping review.BMC Med Educ21, 338 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02644-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02644-5

Keywords

- Postgraduate medical education

- Physicians

- Medical ethics

- 伦理s training program

- 伦理s education

- 伦理s curriculum

- Scoping review

- Systematic scoping review

- SEBA