- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

An online discussion between students and teachers: a way forward for meaningful teacher feedback?

BMC Medical Educationvolume21, Article number:289(2021)

Abstract

Background

Student evaluation is an essential component in feedback processes in faculty and learner development. Ease of use and low cost have made paper evaluation forms a popular method within teaching programmes, but they are often seen as a formality, offering variable value towards the improvement of teaching. Students report poor motivation to engage with existing feedback tools whilst teachers describe receiving vague, contradicting, or irrelevant information.

We believe that feedback for teachers needs to be a two-way process, similar to feedback for students, for it to be effective. An online feedback tool has been implemented for third-year medical students from Imperial College London to promote open discussion between teachers and students. The feedback tool is accessible throughout students’ clinical attachment with the option of maintaining anonymity. We aim to explore the benefits and challenges of this online feedback tool and assess its value as a method for teacher feedback.

Methods

Qualitative data was obtained from both volunteer third-year medical students of Imperial College London and Clinical Teaching Fellows using three focus groups and a questionnaire. Data was analysed through iterative coding and thematic analysis to provide over-arching analytical themes.

Results

Twenty-nine students trialled this feedback tool with 17 responding to the evaluative questionnaire. Four over-arching themes were identified: reasons for poor participation with traditional feedback tools; student motivators to engage with ‘open feedback’; evaluative benefits from open feedback; concerns and barriers with open feedback.

Conclusion

This feedback tool provides a platform for two-way feedback by encouraging open, transparent discussion between teachers and learners. It gives a unique insight into both teachers and peers’ perspectives. Students engage better when their responses are acknowledged by the teachers. We elaborate on the benefits and challenges of public open feedback and approaches to consider in addressing the self-censorship of critical comments.

Background

Meaningful feedback is essential for both faculty development and programme evaluation [1]. Inclusion of the ‘student voice’ within evaluation and development processes can empower students [2], improve academic performance [3], increase learner-satisfaction [2], improve quality of teaching [4] and assist in the professional development of educators [5].

Student feedback gathered through paper evaluation questionnaires completed at the end of a teaching course is a common and easy way of obtaining feedback from large groups [6,7,8,9]. However, for many it has become a formality [1]. Furthermore, there is ongoing debate about the reliability and reproducibility of student feedback [1,10,11]. Students have previously reported feeling rushed to complete paper feedback forms promptly, further compromising the value of comments available to teachers [12].

Anecdotal evidence from working with clinical teaching fellows (CTFs) affiliated with Imperial College London shows that they receive little effective feedback from their teaching evaluations. An online anonymous survey of CTFs has identified ‘non-specific’ feedback, ‘contradicting [student] opinions’ and ‘complaints about issues beyond CTF control’ as significant limitations. Comments from the students suggest that their feedback is never acted upon. Several studies resonate with this: Aslam demonstrates that there is a ‘considerable disagreement among the students’ responses [1]; Svinicki argues that through ‘learned helplessness’ students find little reason to submit feedback which they believe will not affect future teaching [13]; Day reports “questionnaire fatigue” as another reason for poor engagement [6].

In order to optimise the evaluation process, students and teachers must use a means of gathering information that is acceptable to all parties [1]. When constructed well, online tools offer a simple, cost-effective method of collecting feedback from large groups of learners [9]. A study by Shabbir et al. demonstrated a significant increase in the response rate with use of online form compared a paper evaluation form [14]. Online feedback is not a new approach but, to ensure evaluations are valid, responses must be collected at appropriate times, requested throughout teaching programmes, and returned with an adequate response rate [9,11]. Some teachers at Imperial College London have used Mentimeter (an online software in which the audience can respond to questions using smartphones) to evaluate the teaching sessions. The students responded better as there was no further forms or links [15].

作为一个可能的答案,一些常见的问题s when evaluating teaching, we have created an online feedback tool. Though this tool could be used to evaluate any teaching session, it is designed for use by a group of students who have lengthy clinical placements (4 weeks or more) and have regular sessions with a group of teachers.

Context

We piloted the online feedback tool with third-year medical students from Imperial College London attached to Hillingdon Hospital for a ten-week clinical placement. These students had regular teaching sessions on clinical skills, bedside teaching, and lecture-based teaching with local CTFs. CTFs are junior doctors at an early stage of their teaching careers who are keen to develop their teaching skills. They usually have one-year teaching contracts outside of their postgraduate training programmes. In current practice, students give formal feedback to teachers by two different methods: paper evaluation forms given out by the individual teachers after their teaching sessions and the college central feedback tool, Student Online Evaluation (SOLE). SOLE is an online questionnaire circulated by email during the last week of each placement.

The novel online feedback tool

Our vision is to promote dialogue between students and teachers. We believe that feedback for teachers should be a two-way process, as is the case when learners receive feedback [16,17]. Discussions may lead to a better mutual understanding between teachers and students. This encourages deeper, reflective learning for students and enhanced development for teachers [18]. However, the authority and power within a student-teacher relationship often lie with the teacher, thus the same approaches of providing feedback to students may not be practically applicable to teacher feedback [19]. We believe that this online feedback platform may help to ameliorate the impact of this power imbalance.

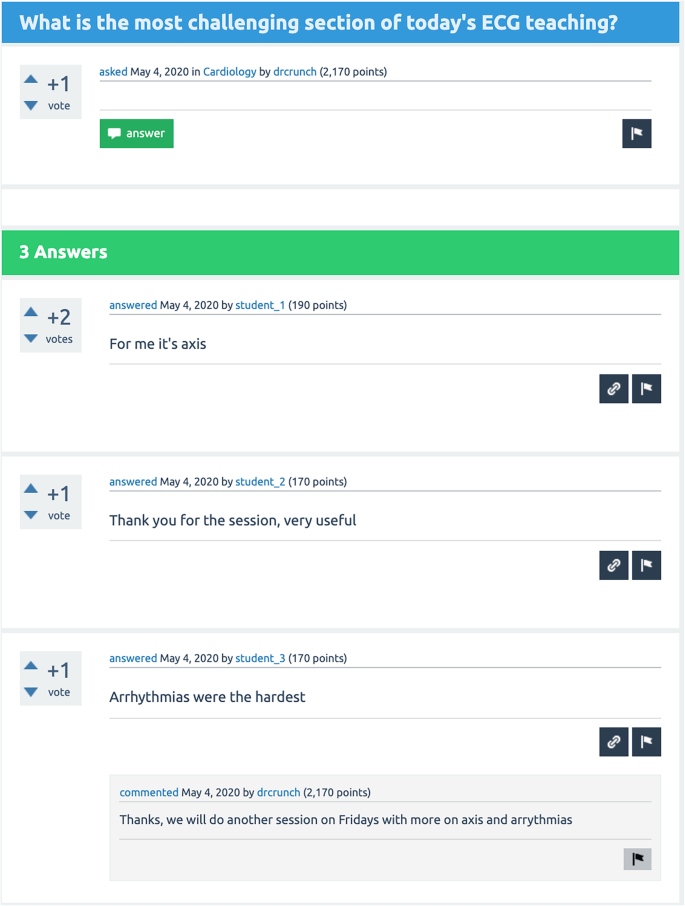

The students are given access to the platform at the induction of their placement. The platform is based on the open-source PHP/MySQL platform Question2Answer (https://www.question2answer.org/).Through this online platform they can post feedback about teaching, ask CTFs questions and make requests regarding future teaching. They can view and annotate each other’s comments and may also agree or disagree with statements by ‘up-voting’ or ‘down-voting’ respectively. CTFs can address the feedback statements with relevant explanations or actions. Students and CTFs can access the tool throughout the placement and students have the option of remaining anonymous when using it. An example of such an online discussion is shown in Fig.1.

Teachers can seek feedback on many educational aspects: the teacher, the content of a teaching session or a whole programme [11]. Control of this tool lies with teachers. When teachers use this tool, they have the option to choose the focus of their feedback by tailoring questions or statements posed to the students. These could include the topic of a future session, a question to evaluate their understanding or a question about a specific aspect of a previous teaching session.

The online conversations between students and teachers or among peers are visible to all the users. We have referred to users’ comments as ‘open’ or ‘public’ to indicate this visibility throughout this paper.

Aims

In this study, we explore the students’ and teachers’ perspectives on the benefits and challenges of this approach and assess the tool’s perceived value to the teachers.

Methods

For this qualitative study, we have adopted a social constructionist view and have embraced a neutral stance to data collection and analysis to explore both the benefits and the challenges of this feedback approach. Balanced analysis facilitates further development of this tool and informs those interested in adopting similar approaches in their own practices.

Study participants and recruitment

The study participants were volunteer third-year medical students from Imperial College London, undertaking a ten-week clinical placement at Hillingdon Hospital from March to May 2018 and clinical teaching fellows who provided regular teaching sessions and used this tool during this attachment. All twenty-nine students on the placement were given access to the online feedback tool from the start of the placement, and engagement with the tool was voluntary. Participants for the focus groups were recruited from amongst these twenty-nine students through advertisements in the student common room and through their undergraduate teaching coordinator. They were rewarded with a certificate of appreciation for their contribution. Ten students (six females, four males) took part in two focus groups which were conducted at the end of the placement. Questionnaires were given out to all students to evaluate the overall view of the cohort and seventeen out of twenty-nine eligible students returned the completed questionnaire.

Data collection

Data were collected from April to May 2018 using questionnaires comprising both closed and open questions, and three focus groups, two with five students each and a third with three teaching fellows. Pre-determined questions were used to guide the discussion resulting in the generation of rich ideas (please see appendix 1 and 2 for the question guides used for students and teachers respectively). The lead researcher acted as the moderator. Discussions were audio-recorded and later transcribed in verbatim by the researchers. All third-year students were given a paper questionnaire with an envelope and were asked to return the filled forms to the teaching coordinator.

Data analysis

Two of the researchers were clinical teaching fellows involved in teaching the participant medical students. The dual role of being a teacher and a researcher can lead to a greater understanding of themes and contextualisation of the data [20]. However, this presented a potential risk of unconscious bias towards magnifying the benefits of the online feedback tool. Nevertheless, having adopted a neutral stance the researchers were equally interested in exploring the challenges and believed in a balanced assessment to establish the effectiveness of this platform. The authors who performed the analysis were not involved in teaching the study participants.

The data was analysed using the framework for thematic analysis as described by Braun & Clarke [21]. Three members of the research team familiarised themselves with the data before generating codes through inductive, open coding processes. With constant comparison and discussion amongst the authors, axial coding ensured codes were assessed for similarities, differences, and duplicates. Two of the authors performed further analysis to generate descriptive themes and categorise associated codes. Each descriptive theme was evaluated with the corresponding data to ensure they correctly reflected the original data. Finally, descriptive themes were assessed to identify over-arching analytical themes. The data from the questionnaire did not add additional themes to those from the focus groups.

Throughout this process, an iterative approach of critical evaluation was encouraged with both individual and group reflections to identify conflicts and discrepancies in codes or themes. Any differences were resolved through discussion and further analysis of data when needed. Prior to advancing from each stage, summaries were distributed amongst the team to ensure that all agreed.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Education Ethics Committee of Imperial College London (MEEC1718–87).

Results

All students created an account for the online feedback tool at their induction, with the option to use a pseudonym if they wished. The response rates were particularly high when CTFs posed a specific question or invited a consensus.

从分析四个首要的主题出现了of our data; from focus groups and questionnaires: 1) reasons for poor participation with traditional feedback tools; 2) student motivators to engage with ‘open feedback’; 3) evaluative benefits from open feedback; 4) concerns and barriers to open feedback. These themes, along with a summary of the associated descriptive narratives and illustrative quotes are shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. In illustrative quotes, ‘a’ and ‘b’ represent the two student focus groups, ‘M’ and ‘F’ denote males and females, respectively. Each male and female student was also given a number to distinguish between focus group members. CTFs were anonymised with a number. Quotes from student questionnaires are identified by ‘SQ’.

Reasons for poor participation with traditional feedback tools (please refer to Table1)

为贫困engageme多个原因被确定nt with paper-based questionnaires and the student online evaluation (SOLE). These included the delay between the experience and giving feedback, the inconvenience of completing the feedback, a lack of purpose in providing feedback and feeling neutral towards the teaching.

Student motivators to engage with open feedback (please refer to Table2)

Student participants described that open feedback allowed teachers to acknowledge and respond to them and establish a dialogue, as well as provide transparency and accountability from faculty. Students also appreciated gaining an insight into faculty thought processes. The immediacy of the teachers’ response generated a perception of personal benefit among students, leading to greater motivation to participate.

Evaluative benefits from open feedback (please refer to Table3)

The faculty appreciated the opportunity to clarify feedback from students and gained further information regarding aspects of teaching. All participants agreed that giving students insight into their teachers’ perspectives would likely lead to greater mutual understanding and foster mutual respect. Participants indicated greater satisfaction with the process when teachers used this information to inform future practice within the timeframe of their clinical placement. Additionally, teachers recognised the opportunity to learn from their peers through comparison and subsequent self-appraisal.

Concerns and barriers to open feedback (please refer to Table4)

研究人员没有发现critical comments or down- votes on the online feedback platform, thus we explored the underlying reasons during focus groups. Many students felt uncomfortable submitting critical feedback, particularly in an open forum. A CTF postulated this might be due to the established rapport between students and teachers over a relatively long period of time. Some students felt deterred from submitting their feedback if their opinion contradicted the consensus. Both student and CTF participants agreed that these could be overcome using anonymous feedback and options to deliver closed feedback directly to an individual. Though there was no critical feedback, teachers were concerned that this would be visible to colleagues and students. CTFs acknowledged that any critical feedback could have an emotional impact and an open forum could amplify this.

Discussion

Our feedback tool offers a novel approach for students and teachers to engage in a dialogue about learning and teaching, going beyond traditional feedback methods.

Challenges of the existing feedback approach

Our observations of shortcomings in existing feedback approaches aligned with those presented in prior literature: delayed requests from teachers for feedback, lengthy feedback forms, no personal benefits perceived by students, student-determined necessity of feedback as perceived ‘really negative’ or ‘really positive’ teaching experiences, ease of offering undiscerning feedback rather than constructive comments, and perceived pressure to respond positively in the presence of a teacher [1,7,12,13]. In the following sections, we have investigated our feedback tool in view of these challenges.

Unique insight into others’ views

The public nature of this approach provides an invaluable insight into the perspectives of teachers, students and of their respective peers. The comments and their weighting (through ‘up-votes’; no ‘down-votes’ received) establish a group opinion, which is more difficult to elicit from individual feedback. Platform users learn about the conflicting requests of students, challenges for teachers, limitations of resources and most importantly, the reasons why some of their feedback is not acted upon. Therefore, student and teacher opinions in an open platform accessible to all are invaluable. Highlighting this benefit, one student participant shared an experience as a member of the student union where unnecessary steps were taken following a request from a demanding student, unaware of the views of the majority. This is further affirmed by a letter published by the students from the same institution highlighting that SOLE feedback is biased as most responses are from students with negative experiences [15]. Though uncomfortable for the student concerned, allowing them to see others’ viewpoints may improve their awareness of the group consensus and gain a better understanding of the wider circumstances.

The study of Robins et al. demonstrates that teachers are more likely accept feedback from students who are engaging and performing academically well [19]. Open group consensus may provide a holistic picture and also guides teachers in choosing future teaching topics, facilitating other teaching improvements, and enhancing student engagement.

Motivation for participation

Teachers’ acknowledgements of their responses and seeing peer contributions incentivises students’ ongoing participation in this dialogue. The transparency and accountability of the process offered a further motivation for students to engage as demonstrated by Dudek at el [18]. Therefore, students’ commitment is closely guided by the teachers’ enthusiasm and drive to respond appropriately and promptly.

我们认为,一个老师的心态也需要适应ing to this new approach, where the feedback process does not end with a teaching session, but the dialogue continues. Some teachers may not foresee the value of investing time responding to students or analysing their comments until they experience the benefits. Setting aside a few minutes each day is helpful. This tool is accessible by all the relevant teaching staff, therefore the demand on a single teacher is less.

Despite earlier literature raising concerns about the accessibility of online systems [12], our experience suggests that online access is no longer an issue in the current digital era where almost all students have access to smartphones or hand-held computers.Unrestrictedaccess to the tool throughout their placement may also have contributed to the better engagement.

Nonetheless, both students and CTF participants believed that easy access to the platform is a key success feature and further development of the tool into a phone or tablet application with one-time log-in would likely enhance engagement.

Public feedback

Despite no critical comments being received, such comments being visible in the public domain was a concern to the CTFs. One could argue that any critical comments can cause an emotional stir, regardless of being private or public. In a private setting, teachers deal with it in isolation while with open feedback, the emotional impact may be heightened but the affected teacher may get support and guidance from their peers. Open feedback can also promote self-reflection amongst other teachers, share good teaching approaches and support planning for future development, similar to the insight that may be gained from participating in the peer review process [22,23].

Lack of critical comments posted on the platform may suggest students were practising self-censorship and this is a concern for the researchers. Several students disliked making contradicting statements or critical comments on a public platform. Therefore, all agreed that a successful tool must have options to send sensitive feedback privately to an individual teacher, the teaching coordinator, or an appropriate person in the university.

In our social norms, we tend to focus our conversations on the positive aspects, especially in ‘formal relationships’ [24]. It is well-known that some teachers avoid giving critical feedback to students for several reasons including damaging relationships [25,26]. We believe that these reasons apply to students, perhaps to an even greater extent, as discussed under ‘power imbalance’ below.

Power imbalance between student and teacher

Whilst not elicited as a concern amongst the students participating in this study, we argue that there are several implicit barriers to providing critical feedback to teachers. Firstly, there are the socio-cultural norms of the student-teacher relationship and the perceived power imbalance, where the authority lies with teachers [22,27]. Secondly, the student-teacher relationship is built over a period, which could favour positively skewed feedback or avoidance of making any critical comments. Thirdly, students could view feedback as a way of showing gratitude or appreciation for their teaching. Olvet et al. demonstrate that medical students are reluctant to provide constructive feedback to the teacher even when feedback is anonymous and has no influence on their future grades. In this study, students have displayed a culture of politeness, softer and passive language with qualifying negative with positive comments known as ‘hedging’ [28]. Reluctance to provide critical feedback is therefore a universal challenge irrespective of the mode of feedback.

We make several suggestions to alleviate the issue. Explaining the purpose and benefits of constructive teaching evaluations and posting guided questions may encourage students. Highlighting the option to post anonymously and assure students that ‘negative’ comment will have no impact on their future teaching or assessment is imperative. Providing guidance on how to formulate feedback to teachers may also empower students [14,19].

Feedback but not feedback: reframing ‘feedback’

We examined the use of this online platform and found that some students accessed it in their own time, away from teaching premises, to respond to certain teacher questions. Interestingly, during our focus group discussions, the students expressed a preference for having allocated time for ‘giving feedback’ within a teaching session. This raised the possibility that the word ‘feedback’ could unnecessarily formalise the process and hinder unbiased open discussion. By asking varied questions on the platform without labelling them as a means of gathering feedback, we argue that student discussion may subsequently increase. In this way, the teacher can direct the conversation to gain a better understanding of the students’ opinions. Rebranding the platform using a word without the historical connotations associated with ‘feedback’ may be a productive way forward.

Limitations

Our sample size was small and therefore may not be representative of the whole student cohort, thus we cannot generalise the findings. Nevertheless, our rich data gave an insight into the use of this tool in our context.

In this study, we focused on teachers receiving feedback through dialogue with students. The validity and reproducibility of the feedback from the students can be influenced by many factors [10]. It is beyond the scope of this study to establish these factors. Further research exploring the reflections of teachers who received both paper-based private feedback and this online approach would be useful to further explore the value of this tool.

As discussed previously, the teachers did not receive any negative feedback from the students. We explored the possible reasons for this behaviour and the suggestions to mitigate such an issue under ‘Power imbalance between student and teacher’. Our discussion is based on our own arguments and related literature.

Conclusion

This online feedback platform has engaged both teachers and learners in a conversation providing insight into each other’s perspectives. Teachers could respond to students’ comments and have the flexibility to direct a focused dialogue and establish a consensus. Students get the unique opportunity to appreciate their peers’ views and contribute to the group discussion. Students’ self-censorship of negative comments could be a universal challenge to any feedback approach while multiple steps could be implemented to mitigate and minimise the effects of public critical feedback. We believe that online platforms encouraging open dialogue can be a way forward for the digital age of teacher feedback.

Availability of data and materials

All the relevant data are included in the manuscript; Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Abbreviations

- CTF:

-

Clinical Teaching Fellow

- SOLE:

-

Student Online Evaluation

References

Aslam锰。学生评价作为一种有效的工具teacher evaluation. J Coll Phys Surg--Pakistan: JCPSP. 2013;23(1):37–41.https://doi.org/10.2013/JCPSP.3741.

Zou D, Lambert J. Feedback methods for student voice in the digital age. Br J Educ Technol. 2017;48(5):1081–91.https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12522.

Cho M, Auger GA. Exploring determinants of relationship quality between students and their academic department: perceived relationship investment, student empowerment, and student–faculty interaction. J Mass Comm Educ. 2013;68(3):255–68.https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695813495048.

Flutter J, Ruddock J. Consulting pupils: What's in it for schools? Oxon: Routledge; 2004.

Flutter J. Teacher development and pupil voice. Curriculum J. 2007;18(3):343–54.https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170701589983.

天k .反馈学习。与卫生行动框架有关:福斯特T,艾德itor. Tutoring and demonstrating: a handbook. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh; 1995. p. 79–88.

Dommeyer CJ, Baum P, Hanna RW, Chapman KS. Gathering faculty teaching evaluations by in-class and online surveys: their effects on response rates and evaluations. Assess Eval High Educ. 2004;29(5):611–23.https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930410001689171.

Avery RJ, Bryant WK, Mathios A, Kang H, Bell D. Electronic course evaluations: does an online delivery system influence student evaluations? J Econ Educ. 2006;37(1):21–37.https://doi.org/10.3200/JECE.37.1.21-37.

Corelli A. Direct vs. anonymous feedback: teacher behavior in higher education, with focus on technology advances. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;195:52–61.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.329.

Hessler M, Pöpping DM, Hollstein H, Ohlenburg H, Arnemann PH, Massoth C, et al. Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1064–72.https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13627.

Fluit CR, Bolhuis S, Grol R, Laan R, Wensing M. Assessing the quality of clinical teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1337–45.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1458-y.

Donovan J, Mader C, Shinsky J. Online vs. traditional course evaluation formats: student perceptions. J Interact Online Learn. 2007;6(3):158–80.

Svinicki MD. Encouraging your students to give feedback. New Dir Teach Learn. 2001;2001(87):17–24.https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.24.

Shabbir A, Raja H, Qadri AA, Qadri MHA. Faculty feedback program evaluation in CIMS Multan, Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12(6).https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8612.

Hamid O, George N, Kothari V. Improving student-faculty feedback: a medical student perspective. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:125–6.https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S183232.

Pendleton D. The consultation: an approach to learning and teaching: Oxford University press; 1984.

Watson MC, Cleland JA, Bond CM. Simulated patient visits with immediate feedback to improve the supply of over-the-counter medicines: a feasibility study. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):532–42.https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp061.

Dudek NL, Dojeiji S, Day K, Varpio L. Feedback to supervisors: is anonymity really so important? Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1305–12.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001170.

Robins L, Smith S, Kost A, Combs H, Kritek PA, Klein EJ. Faculty perceptions of formative feedback from medical students. Teaching Learning Med. 2020;32(2):168–75.https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2019.1657869.

Lichtman M. Qualitative research in education: a User's guide. 3rd ed. California: Sage; 2013.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Sargeant JM, Mann KV, Van der Vleuten CP, Metsemakers JF. Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(3):399–410.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9124-4.

Hammersley-Fletcher L, Orsmond P. Reflecting on reflective practices within peer observation. Stud High Educ. 2005;30(2):213–24.https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500043358.

Fay AJ, Jordan AH, Ehrlinger J. How social norms promote misleading social feedback and inaccurate self-assessment. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2012;6(2):206–16.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00420.x.

Sargeant J, Karen M. Feedback in medical education: skills for improving learner performance. In: Cantillon P, Wood D, editors. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 29.

Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. Jama. 1983;250(6):777–81.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026.

McGarr O, Clifford AM. ‘Just enough to make you take it seriously’: exploring students’ attitudes towards peer assessment. High Educ. 2013;65(6):677–93.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9570-z.

Olvet DM, Willey JM, Bird JB, Rabin JM, Pearlman RE, Brenner J. Third year medical students impersonalize and hedge when providing negative upward feedback to clinical faculty. Med Teacher. 2021:1–15.https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1892619.

Acknowledgements

Professor Susan Smith.

Dr. David Riley.

Dr. Hamish Patel.

Dr. Natalie Kernan.

Dr. Diluxshy Elangaratnam.

Dr. Abirami Rajamanoharan.

Mr. Glen Fernandes.

Ms. Ramya Cooke.

Professor Saroj Das.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH: The lead designer of the work. Collaborated with other authors on ethics application, data collection, analysis of data and interpretation and writing the manuscript. PH: Contributed to literature search, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and writing sections of the manuscript and improving the overall clarity. JF: Contributed to literature search, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and writing the sections of the manuscript. VT: Designing and running the feedback platform. Contributed to ethics application, data collection, transcription, improving the clarity of the manuscript. We went through many drafts until we reached the all agreed final version. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by the Medical Education Ethics Committee of Imperial College London (Reference number: MEEC 1718–87). Participants were recruited on a volunteer basis. They have been given participants information sheets and verbal explanations prior to obtaining their written consent for the study.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from all participants for publication in a medical education journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Question guides for focus groups of students and teachers.

Additional file 2.

Questionnaire on the online feedback tool.

Rights and permissions

Open Access本文是在Creative Commons许可Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hunukumbure, A.D., Horner, P.J., Fox, J.et al.An online discussion between students and teachers: a way forward for meaningful teacher feedback?.BMC Med Educ21, 289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02730-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02730-8

Keywords

- Teacher-evaluation

- Online feedback

- Open discussion

- Challenges

- Two-way feedback

- Undergraduate

- Barriers